The greenroom of the Lorraine Hansberry Theatre was no longer just a backstage retreat—it had become the underground war room of a resistance that history had already seen once before. High windows rattled against February's bitter wind, the sound mixing with the distant hum of construction from the main stage. A thick tension hung in the air, along with Énigme d’Or—one of Vivian LaFarge's signature scents a gift from her mother, created especially for her from Floris of London, its blend of gardenia and magnolia with subtle notes of bergamot unchanged since her mother Marguerite's days in the French Resistance—mingling with the musty sweetness of aging velvet and wood.

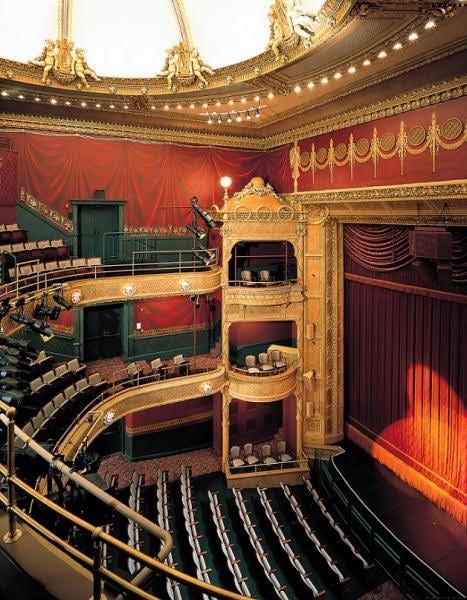

Few people ventured to this particular greenroom anymore. Hidden away in the theatre's east wing, past the maze of narrow corridors lined with decades of show posters, it had become a sanctuary known only to the cast, crew, and most importantly, to Vivian herself. The room's worn art deco moldings and vintage bronze wall sconces spoke to the building's 1920s origins, while the faded velvet curtains—deep burgundy, now more memory than material—had witnessed countless opening nights and closing calls. She had spent decades in this space, first as a young director alongside Claire's grandmother Marie, her closest friend and confidante until Marie's passing last spring. Now it served as their war room, the ghosts of past performances and whispered confidences bearing witness to a different kind of drama unfolding.

Through the frosted glass of the high windows, the city beyond appeared as a series of hostile shadows. Police sirens wailed in the distance, and the occasional thump of helicopter blades cut through the winter air. But here, surrounded by the theater's embracing warmth, the old radiator clicking and hissing in the corner like a drowsy guardian, they had carved out their refuge.

Riley sat at the center table in a 1940s Schiaparelli suit, the surrealist buttons shaped like tiny bronze keys that caught the light. Her oxblood T-strap heels, scored from a vintage shop in the Haight, drummed a quiet rhythm against the floor as she scrolled through article after article, green eyes flickering with barely contained fire. She had read everything. Twice.

Across from her sat Vivian LaFarge, years of elegance and quiet authority wrapped in a perfectly tailored Lanvin suit. She sat straight-backed and tall, her white hair swept back in elaborate twists that spoke of old-world sophistication, her silver-headed cane resting against the table like a conductor's baton. The emerald-and-diamond brooch her mother had smuggled out of Paris caught the light as her elegant fingers traced patterns on the table's surface, each movement deliberate as a conductor's gesture.

Mark, a stagehand who had become more of a soldier than a technician, leaned against the wall, arms crossed, face grim. Claire, streaming in from New York, listened, her expression tight as her laptop cast a bluish glow on her face.

Claire's face filled the laptop screen propped at the end of the table, the dim lighting of Les Deux Canards casting shadows across her face. A long scar traced her jawline—legacy of a protest gone wrong—and her eyes, too knowing for her years, darted between the others as she balanced a serving tray just out of frame. The restaurant's night crowd provided perfect cover for their conversation, just as it had when her grandmother Marie and Vivian had planned their first experimental theatre productions decades ago, their shared passion for both art and justice forming a bond that would span generations. The winter storm that had swept through New York that morning cast occasional shadows across Claire's feed as snow fell past the restaurant's windows.

Vivian LaFarge stood and slowly walked to the end of the table, placing her hands on the old wooden top as she looked at each member of the gathered group, the glow of candlelight reflecting off her mother's brooch. She did not rush. A lifetime of experience had taught her that true power lay in the spaces between words, in the measured pause that let a room lean in.

"They thought they could control him," she said, her Parisian-accented English slicing through the quiet. "The billionaires of America believe they can purchase power, just as the industrialists of Germany once believed they could control Hitler. But power is a beast that does not obey its buyer. It devours."

She tapped her hands lightly against the old wooden table.

"Musk is not merely a financier like the others. He controls the infrastructure itself—the satellites, the networks, the energy grids. While Trump believes he reigns, while he demands fealty from those who once thought they owned him, Musk waits. A predator in the dark."

She looked around the room, her gaze landing on each of them.

"We resist. Not with guns, nor riots, nor speeches on the Senate floor. The age of open defiance has arrived but so has the era of quiet resistance. The art of sabotage in proven acts. The art of the long game." She paused. "Robert Reich wrote about April 19th being the 250th anniversary of Lexington and Concord. Harold Meyerson suggests that on that day we stage massive peaceful protests in every city and town—crowds of Americans celebrating the anti-monarchical uprising of 1775 and pledging their allegiance to that heritage by denouncing Trump's increasingly autocratic rule."

"Vivian, where did you hear that?" asked Claire in a quizzical manner.

Vivian retorted, "I read Robert's Substack, of course. Don't you?" Claire squirmed in her chair appropriately chastened while everyone else muffled giggles and looked at one another whispering "Who knew Vivian reads Substack..."

Riley slammed the laptop shut. "Alright."

Mark blinked. "Alright?"

Riley looked around the room, a new fire in her expression. "It's happening. The coup isn't 'coming'—it's here. And what do we have?" She gestured around them. "A stage. A theater. An audience. And if history tells us anything?" She looked to Vivian now. "That's enough."

Vivian's gaze sharpened. "A coded performance."

Riley grinned. "Exactly."

Vivian's voice took on the weight of history. "During the Nazi occupation, theaters weren't just stages—they were battlegrounds. The people inside them were fighters, saboteurs, spies. In 1944, Jean Anouilh's Antigone was performed in Paris. On the surface? A Greek tragedy. But to the audience? A battle cry. The tyrant Creon represented the Vichy regime, and Antigone? The Resistance. The Nazis let it play, not realizing they were endorsing their own downfall."

"Cabarets were weapons," she continued, her smile sharp. "In Berlin, a comedian named Werner Finck mocked the Nazis to their faces. He was careful—just vague enough. For a while, he got away with it. Then, one day, they dragged him off to Sachsenhausen. But for months, he kept audiences laughing at their oppressors. And that? That was power."

"They used art as a weapon," Claire whispered.

Vivian nodded. "And theaters became underground hubs." She tapped her cane against the floor. "Dressing rooms, trapdoors, orchestra pits—they were all used to smuggle intelligence, hide documents, shelter the hunted. At the Comédie-Française, actors passed coded messages in scripts. At the Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier, Resistance fighters hid documents inside set pieces. And in Amsterdam? Theater costumers forged fake identity papers."

"And when the Nazis took over theaters, do you think they obeyed?" Vivian's eyes burned. "No. Actors forgot their lines. Stagehands misplaced props. Lighting technicians cut the power. In Brussels, Resistance members working in theaters shut off the power during Nazi propaganda films—and blamed it on 'technical difficulties.'"

"Jesus. They fought back," Riley breathed, hands curling into fists.

"They fought with what they had," Vivian said. "And so will we."

"A play within a play," Riley explained, her excitement growing. "They'll think it's glorifying the regime. But to our people? It'll be a message. A blueprint. A way to fight back. We bury the real message in the subtext."

"'The Stage Is Set: A Coup in Three Acts,'" Vivian announced, her cane tapping three distinct times against the floor.

"The first act is the world as it is—the rising danger. The regime in power, the rules tightening, the noose closing in. The illusion of normalcy," Vivian explained. "The second act is the conflict, as the resistance takes form. And the third?" Her fingers curled around her cane. "The rebellion begins in full force."

Outside, the sounds of construction continued, but inside the greenroom of the Lorraine Hansberry Theatre, another kind of building had begun—one that would have made Marguerite LaFarge and Marie Dumont proud. The high windows shuddered against another gust of winter wind, and somewhere in the darkness of the theater's labyrinthine corridors, a door slammed shut, the sound echoing off the century-old brick walls. Beyond their sanctuary, the city grew colder and harder by the day, but here, in this room steeped in history and defiance, the warmth of resistance burned bright.

Vivian rose, every inch the daughter of Marguerite LaFarge, resistance fighter and master of bureaucratic warfare. "They'll think they're watching their triumph," she said, her cultured accent carrying decades of refined danger. Her voice dropped to a whisper. "The Nazis feared theater for a reason. And Trump's regime? They won't see it coming until the final act. Draw up flyers to be handed out about the play at the rallies—the demonstrations on April 19th. We will seem like any other group trying to reach a lot of people quickly. Nobody will suspect a bunch of Gen Zers handing out flyers to be part of any underground resistance group putting on a play to unite people to dismantle the Trump presidency."

THE ART OF QUIET RESISTANCE

Chapter by Chapter

Chapter 1 The Art of Quiet Resistance

Chapter 2 The First Test

Chapter 3 Invisible Movements

Chapter 4 How to Fight the Monsters Under Our Beds

Chapter 5 The Best Disguise is No Disguise

Chapter 6 Midnight and Blue

Chapter 7 The Stage Is Set: A Coup in Three Acts

Chapter 8 Scripts and Subterfuge

Chapter 9 The Secret Code of Us

Chapter 10 The Language of Risk

OSS BRANCH — SIMPLE SABOTAGE FIELD MANUAL Strategic Services

(Provisional) STRATEGIC SERVICES FIELD MANUAL, No. 3

Office of Strategic Services

Washington, D. C.

17 January 1944

This Simple Sabotage Field Manual Strategic Services (Provisional) published as a typewritten manual for the first time, is the information and guidance of all concerned and will be used as the basic doctrine for Strategic Services training for this subject.

The contents of this Manual should be carefully controlled and should not be allowed to come into unauthorized hands.

The instructions may be placed in separate pamphlets or leaflets according to categories of operations but should be distributed with care and not broadly. They should be used as a basis of internal radio broadcasts only for local and special cases and as directed by the theater commander.

AR 380-5, pertaining to handling of secret documents, will be complied with in the handling of this Manual.

William J. Donovan

Section 1. INTRODUCTION

Section 2. POSSIBLE EFFECTS

Section 3. MOTIVATING THE SABOTEUR

Section 4. TOOLS, TARGETS, AND TIMING

Section 5. SPECIFIC SUGGESTIONS FOR SIMPLE SABOTAGE

William J. Donovan had a habit of showing up exactly where history needed him. Soldier, lawyer, diplomat, spymaster—if he’d taken an interest in the culinary arts, we’d probably be crediting him with inventing the CIA and the martini. Best remembered as the founder of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during World War II—the blueprint for today’s CIA—Donovan was the sort of man who made life interesting for both his allies and his enemies.

He was born in Buffalo, New York, on New Year’s Day, 1883, because of course he had to arrive at the start of something. The first-generation Irish-American son of a working-class family, he grew up with the kind of tenacity that makes for great war heroes and absolutely maddening children. At Columbia University, he played football with a level of aggression that probably had his opponents considering career changes. One of his classmates was Franklin D. Roosevelt. One imagines they got along well enough, though FDR likely had the sense to avoid competing with Donovan in anything—a wise choice, given that Donovan approached life like a man who refused to lose.

After law school, he set up shop in Buffalo, where he became a formidable lawyer. He was sharp, ambitious, and had the kind of legal mind that made judges either admire him or reach for the aspirin. But then came World War I, and Donovan was not the type to sit safely behind a desk when there was a war to fight.

He joined the “Fighting 69th” Infantry Regiment, later reorganized as the 165th Infantry of the 42nd Rainbow Division, and—because it was simply how he operated—quickly rose to the rank of colonel. He fought on the Western Front with the kind of courage that makes battlefield legends. At Landres-et-Saint-Georges in 1918, he earned the Medal of Honor for sheer, audacious bravery. He didn’t stop there. He also picked up the Distinguished Service Cross and a handful of foreign decorations, because if Donovan was going to do something, he was going to do it all the way.

After the war, he returned to law, this time serving as U.S. Attorney for Western New York under President Calvin Coolidge. He spent a lot of time prosecuting Prohibition-era bootleggers, though one suspects he had the occasional pang of sympathy for their ingenuity. Later, he became a high-powered corporate lawyer and an international businessman, which sounds ordinary—until you realize that this meant spending a great deal of time in Europe, rubbing elbows with powerful people, and, oh yes, getting very friendly with British intelligence.

By the time World War II rolled around, Donovan was the man who knew everyone, understood everything, and could make himself indispensable in about three sentences. He advised President Roosevelt on intelligence and covert operations, and in 1941, FDR made it official: Donovan became the Coordinator of Information, a fancy title that really meant “America’s first spymaster.” A year later, he transformed that office into the OSS—the United States’ first real intelligence agency. It was the stuff of wartime thrillers: espionage, sabotage, guerrilla warfare, and the kind of psychological operations that would make an enemy lose sleep.

Donovan didn’t just set up the OSS; he reinvented how America did intelligence. He collaborated closely with Britain’s MI6 and the Special Operations Executive, because if there was one thing Donovan knew, it was the value of working with people who’d been in the spy game longer than you. Under his leadership, the OSS trained operatives to infiltrate Nazi-occupied Europe, supported resistance movements in France, Yugoslavia, and China, and turned psychological warfare into an art form. In short, Donovan made sure that American intelligence didn’t just enter the war—it made itself necessary to winning it.

And then, just as he was riding high as America’s top spymaster, the war ended—and Truman, who was deeply suspicious of centralized intelligence, dissolved the OSS. Donovan fought for the creation of a permanent agency, warning that the world didn’t get less dangerous just because the guns stopped firing. In 1947, Truman finally relented, and the CIA was born. But in a classic case of Washington politics, Donovan—who had built the damn thing—was passed over as its first director. The irony must have been bitter, but if he was disappointed, he didn’t show it. Donovan had done what he always did: built something that would outlive him.

He died in 1959 and was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery, having lived the kind of life that most men would need three lifetimes to accomplish. His legacy remains in every intelligence operation the U.S. runs, in every covert mission, in every agent trained in the dark arts of espionage.

And let’s be honest—he would’ve loved that.

Where is our revolt? If it exists it is well disguised.

This is a damn good story, Gloria.